"The harsh reality is that sometimes people you care about will turn their backs on you at any given moment"Froot

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Hololive General

- Thread starter The Proctor

- Start date

Hololive Announcements

Threadmarks

View all 42 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Mio Sololive New Horny Pirate 4M New ENReco Chapter 2 announcement + Axel outfit New Korone's consultation by Miko, Mio, and Subaru New Astel talks about experiences with management New Aki passes 1 million subs New Lui new outfit + cover New Okayu reaches 2 Million subs NewHolo Shop not completely fuck everything up challenge: Impossible.

Apparently you can watch it if you set your VPN to Japan. It's blocked literally everywhere else, though.Oh cool, copyright block by SME

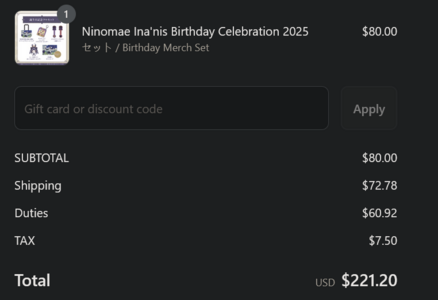

That's gotta be a shipping mistake. There's not even a poster or anything to throw off the dimensions of the package, so what the heck is going on to cause $72 shipping?

ask @Negronald Trump he knowsThat's gotta be a shipping mistake. There's not even a poster or anything to throw off the dimensions of the package, so what the heck is going on to cause $72 shipping?

it probably is just companies being shit and charging more since people will blame it all on the tariffs.

Why are you tards still buying merch if you know your country fucked up all imports?

The 'Duties' section is the tariff, that does nothing to explain the shipping price.ask @Negronald Trump he knows

it probably is just companies being shit and charging more since people will blame it all on the tariffs.

As a comparison I just clicked Shiori's b-day since that's the first other one that I saw on the shop,

$46 is still an excessively high shipping price, but that's nothing compared to $72 for an $80 set with similarly sized products.

Edit: To clarify about the suggestion that it's the shipping company upping prices to take advantage of confusion, I still think that doesn't explain it because of the difference between the charges on these two sets.

Mine's Express CourierThe 'Duties' section is the tariff, that does nothing to explain the shipping price.

As a comparison I just clicked Shiori's b-day since that's the first other one that I saw on the shop,

View attachment 99035

$46 is still an excessively high shipping price, but that's nothing compared to $72 for an $80 set with similarly sized products.

Edit: To clarify about the suggestion that it's the shipping company upping prices to take advantage of confusion, I still think that doesn't explain it because of the difference between the charges on these two sets.

Just move to a country japan ships toAllow me once again to shill Tenso as a service, makes shipping (and committing tax fraud) a lot easier and often times cheaper!

Now if only Japan would actually ship to my fucking country in the first place...

I'd advise against third world countries like America but most are fine.

It's peak.

Oh cool, copyright block by SME

Yeah, trying to go back to watch. Thanks Sony. Even when Cover & Ina has probably paid several thousand dollars for the rights for a maintained copy.

I still don't get the Cover store shipping costs to the USA. Some of the big items, sure. But there's always something wrong with them. Or they don't have a good contract with DHL.

That's gotta be a shipping mistake. There's not even a poster or anything to throw off the dimensions of the package, so what the heck is going on to cause $72 shipping?

This is a consistent problem with their Store. Routing services will end up being cheaper.

The 'Duties' section is the tariff, that does nothing to explain the shipping price.

As a comparison I just clicked Shiori's b-day since that's the first other one that I saw on the shop,

View attachment 99035

$46 is still an excessively high shipping price, but that's nothing compared to $72 for an $80 set with similarly sized products.

Edit: To clarify about the suggestion that it's the shipping company upping prices to take advantage of confusion, I still think that doesn't explain it because of the difference between the charges on these two sets.

Sadly, that seems the most reasonable shipping that Cover has had in a while. I get 35-60USD for a shipment to the States. I don't get some of the small ones with massive costs.

Willemshaven

Outlasted the Chinese Community Sinicization Group

True & Honest Holofan

Joined:

Sep 23, 2023

Lamy, in collaboration with Meiri Shurui sake brewery, had released a new variation of her Yuki-Yo-Zuki, which got announced in December last year. It has won a silver medal of the Sparkling Sake category in the International Wine Challenge 2025. Her previous sake variations from 2022 and 2023 had won the bronze medal in the respective years.

Translation of Lamy's thought behind her previous two sake variations.

Here's an excerpt from the hololive wiki on the new variant. (With many grammatical issues.)

Meiri Shurui said (Google TL):

___

Super Breaking News

The "Bihappou Yuki-Yo-Zuki", developed with Yukihana Lamy, won a silver medal at the world's largest wine and sake tasting event, IWC2025

Finally, Silver in Yuki-Yo-Zuki

It had won two awards in a row, but has now moved up one rank

Congratulations to Lamy!

Thank you everyone for your support!

Translation of Lamy's thought behind her previous two sake variations.

So for anyone who didn’t know, Lamy’s had a partnership with Meiri Shurui (a sake brewery in Ibaraki) since 2021, and together they've released a few limited runs of sake under the brand “Yuki-Yo-Zuki." Translation notes, sake terminology, and extra context below.

NOTES:

0:44 - Homebrewing sake in Japan is very much illegal. So without getting a partnership like this or actually working at a brewery, she probably wouldn’t have ever gotten an opportunity to make sake herself.

1:26 - Sake is generally made with rice that has been polished down to remove the outer layers that contain more proteins, fats, etc., and the amount that you mill away can affect the eventual taste. Sake is also classified by how much the rice was polished, and typically the more polished the rice, the more premium the sake (although that doesn’t at all mean that sake made with less polished rice is worse — they’re just stylistically different). All of Lamy’s sake uses rice that has been polished to 48% (meaning they’ve milled away 52% of the whole rice grain), so they’re considered the most premium and classified as daiginjo/junmai daiginjo.

1:29 - There are a lot of different types of yeast used to brew sake, and they all massively affect the flavor profile due to the aromatics, esters, acids, and such that they produce during fermentation.

1:46 - She uses the term 吟醸香, or "ginjo-ka" to describe the aroma, and it's used to describe sake with a fruit-forward nose. Most commonly associated with sake made from highly polished rice, with yeast that produces fruity-smelling esters like ethyl caproate and isoamyl acetate among others.

2:19 - Sake sort of has a reputation for being an old man’s drink, and younger drinkers are more into wine, beer, chuhai, things that aren’t sake, etc., but there have been more and more breweries pushing things in newer and more exciting directions.

2:46 - To my knowledge, IWC isn’t taken very seriously in the wine world, but the sake division is very well supported by Japanese brewing associations, and the sake judges are extremely legitimate. And anecdotally, I’ve never tried an IWC medalist sake that I thought was bad or just-okay.

One important thing I’d like to clarify here is that a bronze medal doesn’t actually mean third place. For IWC, medals are more like marks of quality, while trophies are what denote the actual champions for each region/class.

At IWC 2022, there were 1732 sake entries. There were 1004 that didn’t medal, 359 bronze medalists, 289 silver medalists, and 80 gold medalists. Out of the 80 golds, 32 won trophies for either class or region.

It’s a lot of awards, but the main thing to note is that if you receive a medal, then at least 12 judges have tasted your sake and agreed that you’ve made a great, quality sake that is representative of its category. So experts agree that Yuki-Yo-Zuki is a good sake! Unfortunately I’ll probably never be able to try it.

3:10 - Meiri usually enters their flagship and a few other sake at IWC every year, and their flagship product has medaled in 2013 (silver), 2015 (gold), 2017 (bronze), 2019 (bronze), 2020 (gold), and 2022 (silver). Even highly prestigious breweries send things to IWC that don’t end up with a medal.

4:38 - When she said well-renowned, she wasn’t joking. I’m 100% certain that the white bottle in that picture is Aramasa X-Type. Cult status brewery, highly sought after, and hard to get ahold of.

5:26 - She says 辛みはこういう数字, which I translated as being “degree of dryness.” The actual measurement is called 日本酒度, or “sake meter value” (SMV) in English. It’s calculated based on specific gravity, which changes with the concentration of residual sugars, and it generally tells you how sweet or dry a sake is.

For those who are unaware, when describing alcohol, dry is meant as the opposite of sweet. It’s not because of the “drying” effect that alcohol has on your mouth, contrary to popular belief, since (for example) a very sweet wine can still come off as drying because of tannins, acids, etc.

5:36 - Nomoto-san uses the term 淡麗辛口, or “tanrei karakuchi” in the appraisal. It describes sake that are light, clean, and dry, which is a very classic profile. We describe this kind of sake as “karakuchi” in English as well, so I swap it in the translation here and there. Meanwhile, “キレが良い” typically describes a clean and pleasantly crisp finish.

6:01 - see above note on “tanrei karakuchi”

6:40 - She glosses over the difference, so I’ll talk about it here. By definition, daiginjo and junmai daiginjo are made with rice that has been polished by over 50%. Daiginjo are made with added brewer’s alcohol to achieve different flavor profiles, while no extra alcohol is added to junmai daiginjo.

6:45 - No. 10 is a type of yeast that’s in a lot of stuff with a classic low-acid, clean and fruity profile (see: Dewazakura, Eiko Fuji, Kudoki Jozu, Kudoki Jozu Jr). M-310 is a variant of No. 10, and it generally produces much more fruity flavors and aromas.

7:06 - Rice variety definitely has some connection to how the sake will taste, but yeast and brewer skill/brewing conditions have a much greater influence. Predictability and controllability for the are big factors in choosing which rice for whichever sake.

7:54 - Kani miso is pasted crab innards, shiokara is seafood fermented in its own viscera, and hiyayakko is cold/seaoned tofu.

13:18 - I dunno how, but I guess I forgot to put the judges’ tasting notes from IWC 2023 in the video here. So here they are: “A Koji and rice malt-driven sake with rose and melon, pollen and cherry blossom. Savoury and fresh.”

Here's an excerpt from the hololive wiki on the new variant. (With many grammatical issues.)

The third Yuki-Yo-Zuki was made to be an entry level sake for beginner. Lamy wanted a sake set that compliment the all-rounder original Yuki-Yo-Zuki and the more personalized Favourite Model. The new model is similar to Favourite Model in term of ingredient but with its alcohol content reduce to 13%. Unique to the new model is the natural fermented light carbonation to allow beginner a more enjoyable experience without affecting those who dislike full sparkling sake hence its name, Bihappou (微発砲, lit. Lightly Sparkling) Yuki-Yo-Zuki. The taste is sweeter and fruitier than the original Yuki-Yo-Zuki. Unlike the other two model, the new model will only be sold in 750ml bottles. A pink bottle is chosen this time to highlight its taste profile.

Last edited:

>the unrecognized country of Somaliland in northern Somalia gets to watch Ina's 3D live

Some intern is getting fired for that>the unrecognized country of Somaliland in northern Somalia gets to watch Ina's 3D live

I find it interesting how JP vtubers tend to tackle the main quest ASAP in Bethesda games.

Threadmarks

View all 42 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Mio Sololive New Horny Pirate 4M New ENReco Chapter 2 announcement + Axel outfit New Korone's consultation by Miko, Mio, and Subaru New Astel talks about experiences with management New Aki passes 1 million subs New Lui new outfit + cover New Okayu reaches 2 Million subs New📧Posting Guidelines📧

- 📁Use Thumbnails. Compress images; use jpgs instead of pngs.

- 💾Keep Archives. See here for tutorials & resources.

- 🔨Report Troublemakers. Do not take bait, avoid disruptive slapfights.

- 🔦Highlight Events! Banner announcements are community-driven. Suggest additions in Community Happenings.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 270

- Views

- 24K

- Sticky

- Replies

- 11

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 501

- Views

- 44K

- Replies

- 20K

- Views

- 1M